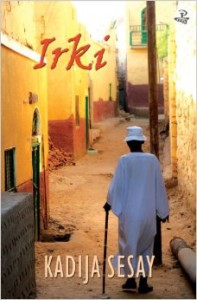

Irki is one of the poetry books published in 2013 that one ought to read before the year ends. Reason, it takes the idea of knitting to a poetic level that becomes crucial in understanding how each individual poem threads into a collection of 53 poems structured under four parts.

Irki is one of the poetry books published in 2013 that one ought to read before the year ends. Reason, it takes the idea of knitting to a poetic level that becomes crucial in understanding how each individual poem threads into a collection of 53 poems structured under four parts.

“Letting Go,” which is Part 1, begins with a journey involving ships–both in the physical and metaphorical space. From the first page, Kadija prepares the reader to begin expecting moving from place to place, continent to continent, seeing and taking note of cultural and racial differences. Grandmothers are important, especially in this section. They too move, and do things differently in an understated manner as portrayed in the poem:

Grandmothers: 1

One chose to lie flat on her narrow wooden bed,

declared, “I won’t be getting up anymore.”

One tried to lie quietly in her castle

through the terror of a civil war.

Grandmother church, grandmother mosque,

gave up their children to the empire.

One to lie flat on a wooden park bench

in London’s Turnham Green.

One to lie on a mattress to yield babies

in exchange for love and dreams.

Part 2 as the section title suggests is about “Rituals.” Initiations. Routines. Remembrances of childhoods. This is by far my favorite section, mostly because of the way Kadija drops into a childlike tone and voice to show us a world in which the speakers are vulnerable, innocent, sensitive, humorous and growing in a tough, sometimes divided world. There are family rituals and then there are rituals. For instance, the last stanza of Family Rituals: Roast rituals/Lamb goes with mint sauce/Pork with apple sauce/Beef with horseradish sauce/Bread goes with dripping/And chips go with custard.

Sunday School, Sunday Roast, my favorite poem in this section captures best the innocence and maturation from childhood. One can see a carefree child, unchained, stomping jubilantly, appropriating gospel songs and remaking her renditions with capital letters and exclamation marks:

I

Sunday school.

Where we learned about Mary, Joseph and Baby Jesus

At birth, he already had a title.

Sunday roast!

My mouth juiced-up with saliva at the imagined smell

of Mum’s dinner on the table.

Never chicken–

that was midweek–would it be slicesofwell-donebeefwithYorkshirepud?

Or pork with chewy crackling?

Meat juice

made roast ‘taters golden–I dreamed of them as I sang out of tune.

Lamb with mint sauce!

II

Sing Hosanna!

Sing Roast Dinner!

Sing Roast Dinner

To the King of Peas!

Sing Hosanna!

Sing Roast Dinner!

Sing Roast Dinner

To Mushy Peas!

Give me joy in my heart

Give me dumpling

Give me joy in my heart I pray

Give me joy on my plate

Keep me thirsting

Keep me gasping

For apple dumpling all day.

III

Lucky us!

After guitar sing-a-longs and Bible stories, we didn’t have far to run.

Our house was opposite the church.

After dumpling–

my fave! Hot and gooey–I shoved a big scoop into my mouth–apple side up.

Then couldn’t pull the spoon out.

Hard choice–

burnt mouth or a bellyfullofappledumplingwithcustard.

The smell went behind my roof, out my nose.

Prayed hard

for God to release me from this pain–and he did speak to me that Sunday–

“Release the apple dumpling!”

It was obvious to me then that God had never tasted apple dumpling

and I never believed in Sunday school in quite the same way, after that.

This poem also reminds me of a story in which the hyena stole a piece of hot meat from man’s fire. The piece was delicious, as one can imagine, even though it burnt the hyena’s mouth. The hyena decided to set forth on a second stealing mission, and a third. This time however, man was clever. He smeared with butter a smooth, slender stone and put it on fire. It glowed red and bright like the previous pieces of meat. The hyena, not knowing it was being tricked, started salivating, then snatched the stone, and held it in its mouth for a while as it tried to make the hard decision between swallowing or spitting. My people say this is what the hyena spoke during hesitation: Mire, mire omuriro, ncwere, ncwere obunuzi. Directly translated as: ‘If I swallow, I swallow fire, if I spit, I spit sweetness/deliciousness.’ The hyena decided to swallow, and the stone/pieceofmeat burnt its throat and stomach severely that it died. Sometimes the hyena wasn’t the hyena but a greedy man.

The other interesting element in this “Rituals” section is the concept and practice of “private fostering.” Apparently, this was common among parents of West African origin, who migrated to the UK in the 1950’s and 60’s. It worked like this: These parents would put their children with English families to care for them, for reasons often related to work, study schedules, or living in places unsuitable to raise children. The experience of children placed with foster families varied greatly, from loving to extreme abuse. The two poems: What’s Blood Got To Do With It: I respect my mother/but do I love her?/It’s a tough one/Which one?/the one who gives birth to you/or the one who looks after you?… and Black Mother/White Mother: Your mother’s here/Zainab dear/come and show her your painting/Don’t look confused/teacher said, bemused/Why are you hesitating?… chronicle these experiences aptly. Several stanzas down we’re shown why the hesitation and the accusatory hiss from Zainab’s mother to the foster mother: This child came from my womb!/You’ve stolen her from me!/She spat out bitterly/Well, she hasn’t seen you for ages!/The onslaught of words/was loudly heard/like tigers snapping across cages…

The last poem in this section, Wedding Photograph reminds me of Susan Kiguli and Margaret Atwood’s photograph poems. Bride in white dress against pale white skin, natural blonde hair piled/into a beehive. Groom in dark suit, black hair, almost as black as my/skin. The dark spot next to Ann–by the bride’s knee–that’s me/The cameraman wasn’t used to just how black black could be. My teeth/ and whites of my eyes shone out!… My brother’s face a shadow of black in his blue suit. That was almost the/end, though we didn’t know it then…

Part III “An African House,” begins with a searing poem, Jamaica Kincaid style. I don’t have to explain it but will let it speak for itself.

This House Is An African House

This house is an African house.

This your body is an African woman’s body.

This your vagina is an African woman’s vagina.

All three, you keep clean, you hear?

Otherwise I will wash you out

with bleach, scrub between your legs

with a scouring pad, then I will take your body

and clean the house with it.

At eleven years old I didn’t want a woman’s body.

I was sure my friends didn’t have vaginas

and I wanted to be just like them.

They weren’t from Africa either.

The last section (part 4) is dedicated to “Homeland.” People as home versus place, place as home versus land, and the imaginary always in between. The collection gets its title, Irki, from the Nubian language, which means homeland. The poems delight and teach, reflect and weigh the loses and gains of growing up in a multicultural global society. To get a copy, click here.

Kadija Sesay is a literary activist of Sierra Leonean descent, editor of SableLit Mag and Amalion Publishing. Her collection is published by Peepal Tree Press.

No comments yet.