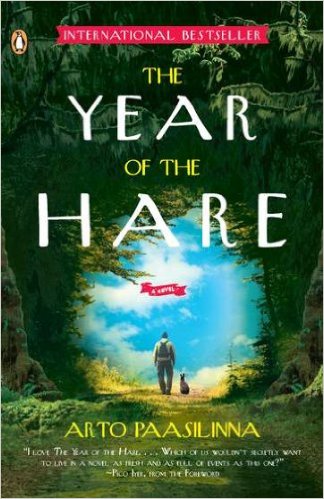

It’s that time of year when I think about the next classes for Spring, and if time permits, beyond Spring. The Year of the Hare by Arto Paasilinna magically fell into my lap while I was browsing. I was skimming through the selected poems of Herbert Lomas online when I saw Arto’s book listed at the bottom of the page. Naturally, being keen on literature that features animals, I ordered the book. This kind of diversion happens a lot in the process of research so I welcome it nowadays–you’re looking for one thing like reading British poetry only to be sidetracked by something else. I also happen to be curious about Finnish/Scandinavian literature so in a way it was an opportunity to feed that interest. I realized that the connection to Lomas was because he had lived in Finland for 13 years and had translated Arto’s book!

It’s that time of year when I think about the next classes for Spring, and if time permits, beyond Spring. The Year of the Hare by Arto Paasilinna magically fell into my lap while I was browsing. I was skimming through the selected poems of Herbert Lomas online when I saw Arto’s book listed at the bottom of the page. Naturally, being keen on literature that features animals, I ordered the book. This kind of diversion happens a lot in the process of research so I welcome it nowadays–you’re looking for one thing like reading British poetry only to be sidetracked by something else. I also happen to be curious about Finnish/Scandinavian literature so in a way it was an opportunity to feed that interest. I realized that the connection to Lomas was because he had lived in Finland for 13 years and had translated Arto’s book!

Arto’s book is delightful, funny and whimsical because it taps into the literature and Finnish tradition that thrive on a journey plot line. The character’s adventurous movements get liberated and complicated episode after episode. The novel is a travel narrative in the picaresque style, utilizing comic, speculative and satirical elements. Pico Iyer, one of the finest travel writers mentions in his foreword to Arto’s book how the story resonates with any one of us who has at some point wished to drop “all the stuff that seems so important–a regular job, a good salary, a solid home–and going off in search of what is really more sustaining: adventure, restoration, fun. To walk, like Thoreau, away from the community one knows too well and to sit still in the forest, where suddenly our companions are the stars, the creatures we’ve never stopped to notice before, other eccentric dropouts, even the pinch of bitter cold…something in us almost cries out for time and freedom and something zesty and close to the ground.” This makes greater sense against a backdrop of modern living, so it’s no wonder that our protagonist, Vatanen, leaves Helsinki city for Finnish Wilderness.

The catalyst to Vatanen’s awakening or moment of epiphany is a wild hare running across the road. This is how it happens: Vatanen is a journalist traveling with a photographer on assignment. Both men are “dissatisfied, cynical and approaching middle age.” The setting sun blinds their eyes and the photographer, who is driving, hits the hare which leaps up in front of the car and hurtles into the forest. Vatanen goes after it, attends to its wounded leg and does not return home. He doesn’t like his wife nor his married life. In the first town he arrives at he makes arrangements with his friend and the bank to sell his boat, transfer some money to his wife while he takes the rest. From then on, he travels through the forests with the hare which he formerly adopts, finds occasional work chopping woods, building cabins, learning about the hare’s special diet and other needs, rescuing a cow from drowning, hunting a bear across the Soviet border, and becoming very resourceful in wilderness living.

Arto’s book also draws on the convention that once required men to journey into the forest to learn wisdom before they could be “men” and return to society as responsible citizens. Thus continuing the spirit of Aleksis Kivi’s 1870 Finnish classic, Seven Brothers. There’s conflict, magic and freedom, reindeer herdsmen, crazy sacrifice and some drinking! which make me think of the African literary tradition in Amos Tutuola‘s novels, most especially, The Palm Wine Drinkard and My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. The structure of Tutuola’s novels utilizes the folk tale in the sense that before the protagonist can be somebody, usually a man, he spins a yarn venturing into the forests and overcoming all kinds of trials. The anti-hero returns a hero. Identity in the modern, industrial, capitalist world versus wild nature is a big deal. Here we can also think of the incredible picaresque and widely translated English novel, Robinson Crusoe, 1719, once heralded as the beginning of the English novel but other beginnings have been sited since then. Other old literatures like Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Mark Twain) and Don Quixote (Miguel de Cervantes) also come to mind. The Book of the Hare was first published in 1975 and demonstrates that for the physical journey to make sense, it must involve internal transformation. Featuring the hare as Vatanen’s one true companion makes it a sweet and highly entertaining read.

No comments yet.