David Whyte in his book, Crossing the Unknown Sea, suggests that, “at the threshold of loss, we look back to gain a glimpse of the nature of anything we have ever held in our hands.” After reading several works of Ali Smith: Hotel World, The Whole Story and Other Stories, The First Person and Other Stories, Shire, Like, The Accidental, in addition to five other books mentioned in previous posts, the quote from Whyte aptly defines the angle of Ali Smith’s work. One could almost say that loss is her thing. It involves people and things that have mysteriously disappeared, died, or are estranged. Artful is the best book, which on one hand, emphasizes how to engage with loss creatively, and on the other presents loss from a philosophical standpoint: everything is already lost. What can a writer or anyone engaged with art do about it? From an inventive point of view, loss is even necessary : we lose words in order to create room for new ones, to discover the essence of art (work) and life, to see what emerges in the gaps. The individual who is faced with loss finds windows of freedom via three aspects: accidents of chance, play, and synchronicity. It appears that Smith’s work relies on these aspects for it to be meaningful. They are the cracks that loosen the structure for new possibilities and choices to break through.

Consider form, for instance. One needs it as a foundation, but until you break it creatively, you may not see the potential or capabilities of formlessness, and the magic or dynamism that emerges as an essential part of the new process. One needs edges to understand limits and freedom, to experience the in-betweenness of things. With Ali Smith, the center is always shifting both in structure and characters. Because of this, distinguishing between major and minor characters can be unfruitful because it’s not the point. Liminality is what’s crucial. Sandor Klapcsik says, “The play of liminality is often associated with the ambiguity of the center… Derrida argues that the appearance and disappearance of a center, its interiority and exteriority, create a constant game in the structures of human reasoning.” Language is where Ali Smith plays the most, making and breaking words and therefore things. Shire, for instance, celebrates the spirit of Milton, who was a great maker-up of words. One of the greatest neologists, he’s said to have introduced into the English language 630 words, “ahead of Ben Jonson with 558, John Donne with 342 and Shakespeare with 229.” Some of these words include, “liturgical, debauchery, besottedly, unhealthily, padlock, dismissive, terrific, embellishing, fragrance, didactic, love-lorn,” and so on.

In language is Smith’s freedom to play with gender as well. Building on the previous examples I’ve mentioned in earlier posts, in The Universal Story, published in “The Whole Story and Other Stories” the narrator tells us:

There was a man dwelt by a churchyard.

Well, no, okay, it wasn’t always a man; in this particular case it was a woman. There was a woman dwelt by the churchyard.

Though, to be honest, nobody really uses that word nowadays. Everybody says cemetery. And nobody says dwelt any more.

We not only have an unreliable narrator but also the beginning of a story that pushes storytelling conventions beyond limit by starting with serious play, uncertainty, while plunging the reader into liminality right away. Here we can suspend our expectations, if we had any, and go with the flow, in short, the possibilities and decisive moments that will keep opening up. Here we can engage with criticism in a manner that allows our judgments to be informed by the work itself as we realize its potential.

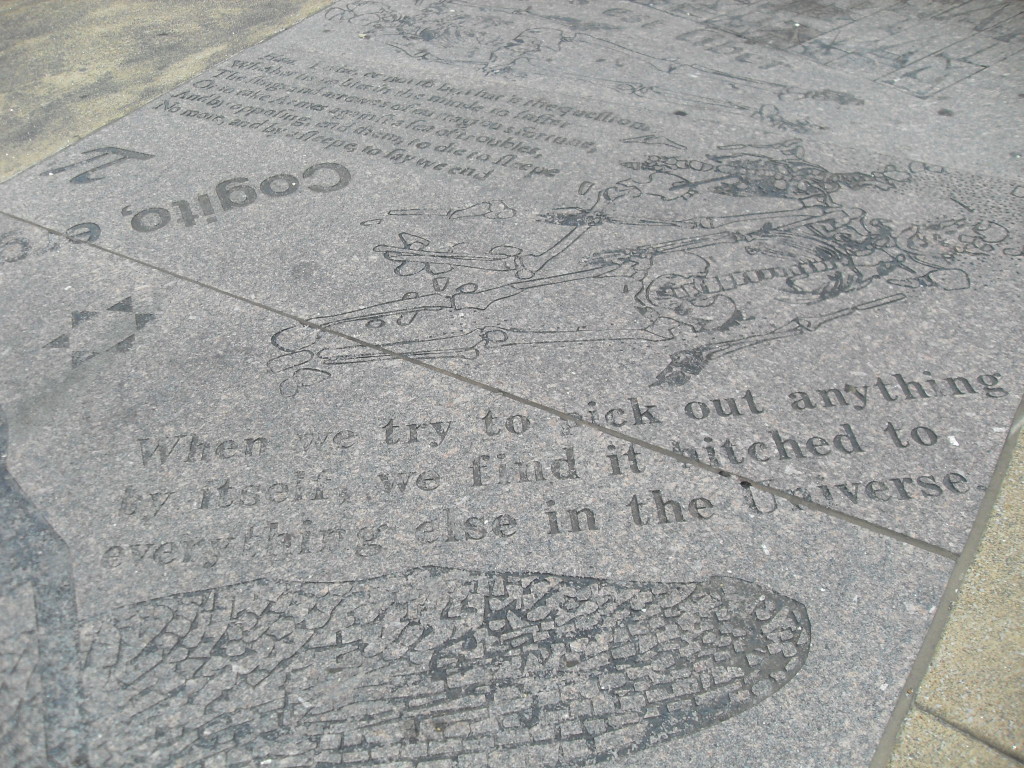

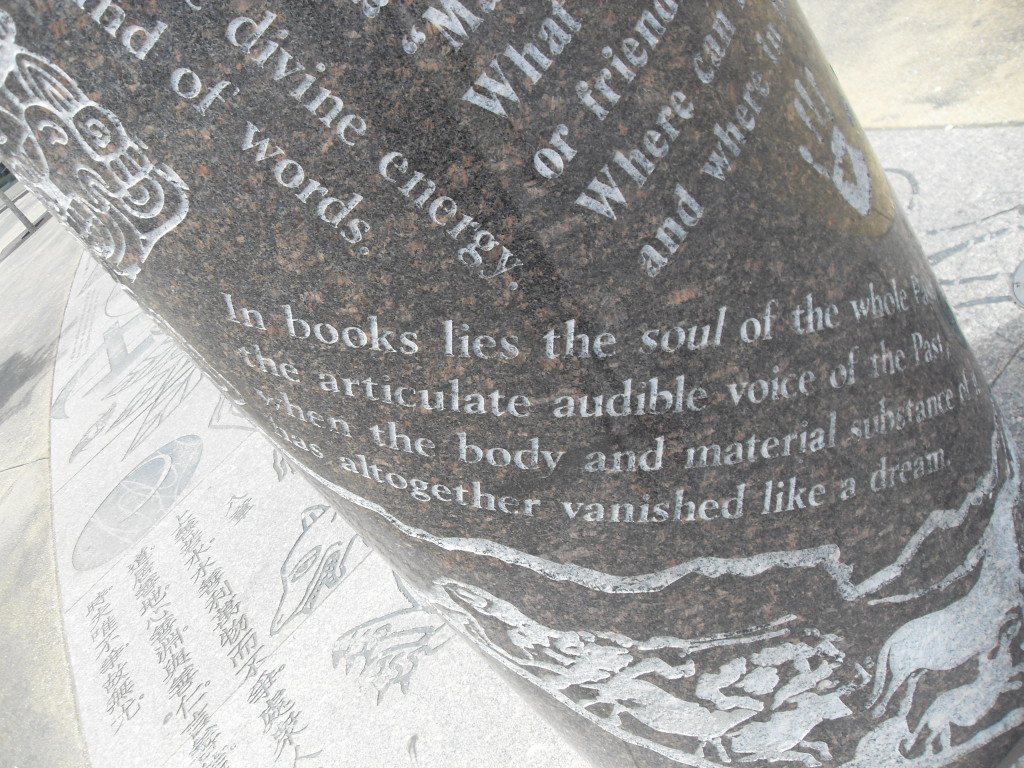

In The Universal Story, there’s a woman who buys all the copies of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, about 500, from various second-hand bookshops and builds a seven-foot boat out of them. Reason, she likes making boats out of things boats aren’t usually made out of. She’s recreating her own Gatsby, so to speak. When her boat is finished, she launches it and it stays afloat for “three hundred yards before it finally [takes] in water and [sinks].” Meanwhile, one of the second-hand bookshop owners who has sold all the copies of The Great Gatsby is delighted, her heart light, floating in her happiness as she replaces the copy that was in the display window with Dante’s The Divine Comedy. It’s hard not to laugh at this. The things that make us happy bring on complex, mixed feelings. Can we be angry at the woman who has destroyed several copies of The Great Gatsby to attain her happiness? Can we criticize the bookseller for her naivety? How do we separate creation from destruction? If we knew the reasons people do certain things, would we stop them from accomplishing their missions? From an ontological perspective, what do all these elements tell us about our status as human beings?

In the postmodern world in which Ali Smith thrives, we are “not simply gendered in one way but in several ways,” as Eric Gould says. “There is always uncertainty and active deconstruction in play and the uncertainty and openness to interpretation drive us to see boundaries as working propositions at best…” We have a scale of ethics on one hand, and aesthetics on the other. Smith introduces us to ambivalence in art, but at the same time refracted in life. This dimension seems to highlight her choice of hybrid in genre as well. The nature of experience, not just writing, cuts across. Who can experience life as just poetry, period. Just prose, drama, art, and so on? When characters are truly living their lives, they’re existing in all these fields and that is what makes hybridization a form/vehicle that could be more true (if truth is our interest) to life and art than any other specified genre. Returning to us as humans [characters], Eric Gould says in relation to Ali Smith, “We are not just here or there. We’re potentially everywhere.” This is the thread that Smith weaves throughout her works, and liminality is the space through which we can travel and explore notions of being, ethics, politics, aesthetics, erotics, myth, identity, gender, and so on.

To expound on the genre quandary through definitions, True short story in “The First Person and Other Stories” collection, describes two men in the cafe discussing the difference between the novel and the short story. “A flabby old whore,” the older man says of the novel, and his companion, a younger fellow, responds, “She was serviceable, roomy, warm and familiar… but really used up, really a bit too slack and loose.” In contrast, the short story “was a nimble goddess, a slim nymph. Because so few people had mastered the short story she was still in very good shape.” The narrator, listening to the conversation, decides to phone a friend who is an expert on the short story and get confirmation. She sees the chance of a potential thesis out of curiosity, fun, or both. Her friend replies, taking us into a world of mythology and eros in exploration of the short story, “A short story is like a nymph because satyrs want to sleep with it all the time. A short story is like a nymph because both like to live on mountains and in groves and by springs and rivers and in valleys and cool grottoes. A short story is like a nymph because it likes to accompany Artemis on her travels…” Eventually, we leap into what other writers have said about the short story:

Franz Kafka–the short story is a cage in search of a bird.

Tzvetan Todorov–it’s so short it doesn’t allow us the time to forget that it’s only literature and not actually life.

Nadine Gordimer–short stories are absolutely about the present moment, like the brief flash of a number of fireflies here and there in the dark.

Elizabeth Bowen–the short story has the advantage over the novel of a special kind of concentration, and that it creates narrative every time absolutely on its own terms.

Eudora Welty–short stories often problematize their own best interests and that is what makes them interesting.

Henry James–the short story, being so condensed, can give a particularized perspective on both complexity and continuity.

Jorge Luis Borges–short stories can be the perfect form for novelists too lazy to write anything longer than fifteen pages.

Walter Benjamin–short stories are stronger than the real, lived moment, because they can go on releasing the real, lived moment after the real, lived moment is dead.

Alice Munro–every short story is at least two short stories.

This goes on until we get to the question: “So when is the short story like a nymph?”

And the answer: “When the echo of it answers back.”

“The First Person and Other Stories” as a collection carries on the element of linguistic play and performance. The third person story, like the second person, for instance, gives us something in line with narrative viewpoint, and also what’s completely different and unrelated to voice and style, but makes sense in terms of numbers, that is, how many persons are in the story or being addressed. But then, even that isn’t followed consistently. Stability isn’t in the works, Smith is always stripping the ground from beneath our feet. fidelio and bess, in connection with what we looked at earlier in How to Be Both and Girl Meets Boy, reverses gender identities and cross-dressing, while present, could be an acknowledgment of either what’s existing in a moment, place, time, the action being expressed in a grammatical sense, or what’s given, portrayed and denied. All these interpretations are possible.

Then we have the what-if kind of liminal that resides in fantasy. the child, is a good example. A woman is shopping at Waitrose, leaves her trolley by the vegetables to pick up something from another section and when she returns to her trolley, there’s a child sitting in it. At first she thinks it’s not her trolley, but looking closely at the items, besides the child, they’re definitely hers. She waits for someone to claim the child until she decides to wheel it to the Customer Services, where a woman named Marilyn Monroe, yes, that’s the name on her badge, praises the loveliness of the child and even suggests that he’s like the mother, who isn’t, and soon other customers think that the woman with the trolley is indeed the mother of the child. All her efforts to explain that she isn’t are in vain. Nothing via intercom has reported a missing child. When the child raises its little fat arms in the air and starts crying amidst Mummaam sounds, one of the customers lifts the child up and shoves it in the “mother’s” arms. Immediately it stops crying, puts its arms around the woman, who by now is embarrassed but is consoled by the crowd around her. “You don’t need to be scared, love. Such a pretty child,” a passing woman says. “Go on home, love” an old man says. “Give him his supper and he’ll be right as rain.” Another woman says, “Teething… It can drive you crazy but it’s not forever. Don’t worry. Go home now and have a nice cup of herb tea and it’ll all settle down, he’ll be asleep as soon as you know it.” And so she decides to go home with the child, thinks of deserting it by the bins or somewhere else, then changes her mind, but when the child starts speaking obscenities, it’s no longer a bad idea to abandon it.

In “The Whole Story and Other Stories” collection, another strange incident happens. A man falls in love with a tree, in the story, may. Since the tree isn’t in his yard, he has to trespass in order to be with it. When the owner of the tree informs the police who restrain the man, at night he sneaks out of his home, leaves his wife asleep and goes to be with the tree. When the wife finds out, she’s relieved, even delighted, that her rival doesn’t have genitals! believe me also plays with liminal fantasy in another direction. A character suggests that she’s having an affair, and invents a whole other family complete with children and in-laws. Her companion knows that she’s making believe, and indulges her in the details, if for nothing else, then for the sake of keeping their own fire burning to eliminate becoming stuck in their union.

No comments yet.