I’d forgotten how beautiful this story is by Ama Ata Aidoo. Told simply and boldly.

I’d forgotten how beautiful this story is by Ama Ata Aidoo. Told simply and boldly.

I remember reading Ama’s other story: She Who Would Be King—another great one–and admiring her vision for women’s top leadership positions. That was before any country in post-colonial Africa had a female president. A few years down the road, (in 2005), Liberia elected the first female president. For me, in addition to writing great stories, Ama is also a prophet.

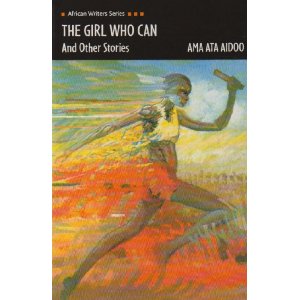

The Collection in which the story appears, The Girl Who Can and Other Stories, was published by African Writers Series in 1997. The short story also appears in an Anthology of Contemporary African Women’s Writing edited by Yvonne Vera, 1999, under the African Writers Series. Yvonne Vera said of The Girl Who Can short story: “…rich with satiric observation. Aidoo criticizes the politics surrounding the female body in cultural practice…”

Here’s the story:

They say I was born in Hasodzi; and it is a very big

village in the central region of our country, Ghana. They

also say that when all of Africa is not choking under a

drought, Hasodzi lies in a very fertile lowland in a district

known for its good soil. Maybe that is Why any time I don’t

finish eating my food, Nana says, “You Adjoa, you don’t

know what life is about . . . you don’t know What problems

there are in this life . . .”

As far as I could see, there was only one problem. And it

had nothing to do with what I knew Nana considered as

“prob1ems,” or what Maami thinks of as “the problem.”

Maami is my mother. Nana is my mother’s mother. And

they say I am seven years old. And my problem is that at

this seven years of age, there are things I can think in my

head, but Which, maybe, I do not have the proper language

to speak them out with. And that, I think, is a very serious

problem because it is always to decide whether to

keep quiet and not say any of the things that come into my

head, or say them and get laughed at. Not that it is easy to

get any to listen to you, even when you decide to

take the risk and say something serious to them.

Take Nana. First, I have to struggle to catch her

attention. Then I tell her something I had taken a long

time to figure out. And then you know what always

happens? She would at once stop whatever she is doing

and, mouth open, stare at me for a Very long time. Then,

bending and turning her head slightly, so that one ear

comes down towards me, she’11 say in that voice: “Adjoa,

you say what?” After I have repeated whatever I had said,

she would either, still in that Voice, ask me “never, never,

but NEVER to repeat THAT,” or she would immediately

burst out laughing. She would laugh and laugh and laugh,

until tears run down her cheeks and she would stop

whatever she is doing and wipe away the tears with the

hanging edges of her cloth. And she would continue

laughing until she is completely tired. But then, as soon as

another person comes by, just to make sure she doesn’t

forget Whatever it was I had said, she would repeat it to

her. And then, of course, there would be two old people

laughing and screaming with tears running down their

faces. Sometimes this show continues until there are three,

four, or even more of such laughing and screaming tear-

faced grown-ups. And all that performance for whatever I’d

said? I find something quite confusing in all this. That is,

no one ever explains to me why sometimes I shouldn’t

repeat some things I say; while at other times, some other

things I say would not only be all right, but would be

considered so funny they would be repeated so many times

for so many peop1e’s enjoyment. You see how neither way of

hearing me out can encourage me to express my thoughts

too often?

Like all this business to do with my legs. I have always

wanted to tell them not to worry. I mean Nana and my

mother. It did not have to be an issue for my two favorite

people to fight over. I didn’t want to be told not to repeat it

or for it to be considered so funny that anyone would laugh

at me until they cried. After all, they were my legs . . .

When I think back on it now, those two, Nana and my

mother, must have been discussing my legs from the day I

was born. What I am sure of is that when I came out of the

land of sweet, soft silence into the world of noise, the first

topic I met was my legs.

That discussion was repeated very regularly.

Nana: “Ah, ah, you know, Kaya, I thank my God that

your very child is female. But Kaya, I am not sure

about her legs. Hm. . . hm . . . hm . . .”

And Nana would shake her head.

Maami: “Mother, why are you always complaining

about Adjoa’s legs? If you ask me . . .”

Nana: “They are too thin. And I am not asking you!”

Nana has many voices. There is a special one she uses

to shut everyone up.

“Some people have no legs at all,” my mother would try

again, with all her small courage.

“But Adjoa has legs,” Nana would insist; “except that

they are too thin. And also too long for a woman. Kaya,

listen. Once in a while, but only once in a very long while,

somebody decides-nature, a child’s spirit mother, an

accident happens, and somebody gets born without arms,

or legs, or both sets of limbs. And then let me touch wood; it

is a sad business. And you know, such things are not for

talking about everyday. But if any female child decides to

come into this world with legs, then they might as well be

legs.”

“What kind of 1egs?” And always at that point, I knew

from her voice that my mother was weeping inside. Nana

never heard such inside weeping. Not that it would have

stopped Nana even if she had heard it. Which always

surprised me. Because, about almost everything else apart

from my legs, Nana is such a good In any case,

what do I know about good grown-ups and bad grown-ups?

How could Nana be a good grown-up when she carried on

so about my legs? All I want to say is that I really liked

Nana except for that.

Nana: “As I keep saying, if any woman decides to come

into this world with her two legs, then she should select

legs that have meat on them: with good calves. Because you

are sure such legs would support solid hips. And a woman

must have solid hips to be able to have children.”

“Oh, Mother.” That’s how my mother would answer.

Very, very quietly. And the discussion would end or they

would move on to something else.

Sometimes, Nana would pull in something about my

father:

How, “Looking at such a man, we have to be humble

and admit that after all, God’s children are many . . .”

How, “After one’s only daughter had insisted on

marrying a man like that, you still have to thank your God

that the biggest problem you got later Was having a

granddaughter With spindly legs that are too long for a

woman, and too thin to be of any use.”

The way she always added that bit about my father

under her breath, she probably thought I didn’t hear it. But

I always heard it. Plus, that is what always shut my

mother up for good, so that even if I had not actually heard

the words, once my mother looked like even her little

courage was finished, I could always guess what Nana had

added to the argument.

“Legs that have meat on them with good calves to

support solid hips . . . to be able to have children.”

So I wished that one day I would see, for myself, the

legs of any woman who had had children. But in our

village, that is not easy. The older women wear long wrap-

arounds all the time. Perhaps if they let me go bathe in the

river in the evening, I could have checked. But I never had

the chance. It took a lot of begging just to get my mother

and Nana to let me go splash around in the shallow end of

the river with my friends, who were other little girls like

me. For proper baths, we used the small bathhouse behind

our hut. Therefore, the only naked female legs I have ever

seen are those of other little girls like me, or older girls in

the school. And those of my mother and Nana: two pairs of

legs which must surely belong to the approved kind;

because Nana gave birth to my mother and my mother

gave birth to me. In my eyes, all my friends have got legs

that look like legs, but whether the legs have got meat on

them . . . that I don’t know.

According to the older boys and girls, the distance

between our little village and the small town is about five

kilometers. I don’t know what five kilometers mean. They

always complain about how long it is to walk to school and

back. But to me, we live in our village, and walking those

kilometers didn’t matter. School is nice.

School is another thing Nana and my mother discussed

often and appeared to have different ideas about. Nana

thought it would be a waste of time. I never understood

what she meant. My mother seemed to know-and

disagreed. She kept telling Nana that she–that is, my

mother-felt she was locked into some kind of darkness

because she didn’t go to school. So that if I, her daughter,

could learn to write and read my own name and a little

besides-perhaps be able to calculate some things on

paper-that would be good. I could always marry later and

maybe . . .

Nana would just laugh. “Ah, maybe with legs like hers,

she might as well go to school.”

Running with our classmates on our small field and

winning first place each time never seemed to me to be

anything about which to tell anyone at home. This time it

was different. I don’t know how the teachers decided to let

me run for the junior section of our school in the district

games. But they did.

When I went home to tell my mother and Nana, they

had not believed it at first. So Nana had taken it upon

herself to go and “ask into it properly.” She came home to

tell my mother that it was really true. I was one of my

school’s runners.

“Is that so?” exclaimed my mother. I know her. Her

mouth moved as though she was going to tell Nana, that,

after all, there was a secret about me she couldn’t be

expected to share with anyone. But then Nana herself

looked so pleased, out of surprise, my mother shut her

mouth up. In any case, since they heard the news, I have

often caught Nana staring at my legs with a strange look

on her face, but still pretending like she was not looking.

All this week, she has been washing my school uniform

herself. That is a big surprise. And she didn’t stop at that,

she even went to Mr. Mensah’s house and borrowed his

charcoal pressing iron. Each time she came back home with

it and ironed and ironed and ironed the uniform, until, if I

had been the uniform, I would have said aloud that I had

had enough.

Wearing my school uniform this week has been very

nice. At the parade, on the first afternoon, its sheen caught

the rays of the sun and shone brighter than anybody e1se’s

uniform. l’m sure Nana saw it too, and must have liked it.

Yes, she has been coming into town with us every afternoon

of this district sports week. Each afternoon, she has pulled

one set of fresh old clothes from the big brass bowl to Wear.

And those old clothes are always so stiffly starched, you can

hear the cloth creak. But she walks way behind us

schoolchildren. As though she was on her own way to some

place else.

Yes, I have won every race I ran for my school, and I

have won the cup for the best all-round junior athlete. Yes,

Nana said that she didn’t care if such things are not done.

She would do it. You know what she did? She carried the

gleaming cup on her back. Like they do with babies. And

this time, not taking the trouble to walk by herself.

When we arrived in our village, she entered our

compound to show the cup to my mother before going to

give it back to the headmaster.

Oh, grown-ups are so strange. Nana is right now

carrying me on her knee, and crying softly. Muttering,

muttering that: “saa, thin legs can also be useful . . .” that

“even though some legs don’t have much meat on them . . .

they can run. Thin legs can run . . . then who knows? …”

I don’t know too much about such things. But that’s how

I was feeling and thinking all along. That surely, one

should be able to do other things with legs as Well as have

them because they can support hips that make babies.

Except that I was afraid of saying that sort of thing aloud.

Because someone would have told me never, never, but

NEVER to repeat such words. Or else, they would have

laughed so much at what I’d said, they would have cried.

It’s much better this way. To have acted it out to show

them, although I could not have planned it.

—

One Response to The Girl Who Can…