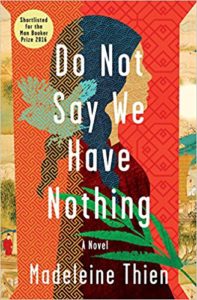

Do Not Say We Have Nothing, is the most ambitious novel I’ve so far read this year. Madeleine Thien’s 2016 Man Booker finalist is not only ambitious in its narrative structure but also in its memorialization and retelling of the Cultural Revolution of Mao Zedong’s communist regime. Lovers of fat historical novels will enjoy this book and those who have an affinity for music. In fact, music is a major part of what holds the book together from the beginning to the end, and what connects various characters across time and generations. Consider this:

Do Not Say We Have Nothing, is the most ambitious novel I’ve so far read this year. Madeleine Thien’s 2016 Man Booker finalist is not only ambitious in its narrative structure but also in its memorialization and retelling of the Cultural Revolution of Mao Zedong’s communist regime. Lovers of fat historical novels will enjoy this book and those who have an affinity for music. In fact, music is a major part of what holds the book together from the beginning to the end, and what connects various characters across time and generations. Consider this:

Swirl was humming a fragment of music, a small piece of the unending sonata that Sparrow had written. Big Mother took the words from “Song of the Cold Rain,” from “In That Remote Place,” and joining in, sang them over Swirl’s music. The melodies came from songs and poems Ai-ming half recognized, songs her father had sung when she was a child. The harmony was rich and also broken, because the two women were so much older now, and they had loved and let go of so many things, but still the music and its counterpoint remained.

Even for the characters that perish, music survives them.

At some point, the narrator wonders whether there’s ever the making of new music or a continuous enlargement of the music that’s already there. The narrator says:

Just recently, I began listening to the transcriptions and reimagining of Bach’s music written by the Italian pianist Ferrucci Busoni… Two hundred years separate the births of Bach and Busoni, yet I find these transcriptions intricate and terribly beautiful. Why did Busoni transcribe Bach? How does a copy become more than a copy? Is art the creation of something new and original, or simply the continuous enlargement, or the distillation, of an observation that came before?

The answer to this is found in another art form that layers and complicates the book’s plot line, that is, the reading and writing of the mysterious Book of Records. In brief, the story of the Book of Records within Thien’s story is a continuing and unending tale between two main characters, May Fourth who journeys across the Gobi desert and Da-wei who crosses the seas to America. The book has no known author and we get into it beginning with Volume 17, then other volumes start to appear thereafter. At some point, Thien’s characters take over the narrative and reproduce more volumes by putting themselves in the book. At the height of the cultural revolution when it is dangerous to be found with counter-revolutionary literature, Swirl and Wen the Dreamer, “real” characters in Do Not Say We Have Nothing, code themselves and their own journeys within the latter volumes of the Book of Records. That way they’re able to trace and reunite with each other. Like the legendary May Forth and Da-wei, Swirl and Wen escape China and traverse the desert.

This narrative strategy brings to mind J.J. Abrams inventive novel, S. that tells a story within a story–the Ship of Theseus novel on one hand, and on the other, the narrative of two college students who are reading the novel and trying to piece together the author, while communicating with one another in the novel itself via handwritten notes in the margins and other materials like maps and letters inserted in the novel. This embedded story aspect in Do Not Say We Have Nothing is probably the most experimental part and at some point towards the middle of the book it begins to flounder but luckily does not completely crash under its own weight because of the emotional investment in the characters. In the end, the narrator determines to populate the fictional world–the Book of Records–with the true names and deeds of the dead where they would “live on, as dangerous as revolutionaries but as intangible as ghosts.”

If you’ve plowed through Peter Weiss’ 1000 paged three-part novel: The Aesthetics of Resistance, Thien’s 463 pages will be nothing and yet offer so much in correlation, as both books deal with the fragile beauty and survivance of a people during revolutions and historical conflicts that threaten to destroy art and culture. How do the collective masses come by liberation? What is the true nature of freedom? Where is redemption when a lot of blood is shed and almost no one survives unscathed? How do future generations deal with intergenerational trauma and still trust that anything good could ever come out of political propaganda disguised as revolution?

I’ll end this review with a passage on the saving grace that characters find in music in spite of their incredible heartbreaks, and how, even amidst grief, joy surprisingly seeps into musical compositions.

At first, the violin played alone, a seam of notes that slowly widened. When the piano entered, I saw a man turning in measured, elegant circles, I saw him looking for the centre that eluded him, this beautiful centre that promised an end to sorrow, the lightness of freedom. The piano stepped forward and the violin lifted, a man crossing a room and a girl weeping as she climbed a flight of steps; they played as if one sphere could merge into the other, as if they could arrive in time and be redeemed in a single overlapping moment. And even when the notes they played were the very same, the piano and violin were irrevocably apart, drawn by different lives and different times. Yet in their separateness, and in their quiet, they contained one another.

No comments yet.