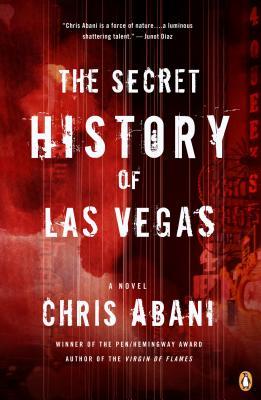

Book Review of The Secret History of Las Vegas

Sometime in the summer I wanted to read books that delight, entertain and also instruct in a subtle way. Pede Hollist suggested Chris Abani, and I realized he had been on my list for many years but I never quite got to reading him.

Sometime in the summer I wanted to read books that delight, entertain and also instruct in a subtle way. Pede Hollist suggested Chris Abani, and I realized he had been on my list for many years but I never quite got to reading him.

I started with The Secret History of Las Vegas and was pleased to find it lovely. Besides the story being fascinating and mysterious–among other things it involves conjoined twins named Fire and Water (elemental in every way imaginable) who may or may not be psychopaths, the most engaging aspect is that those who are busy studying them end up revealing the depth of their own demons. The position of the book in the genre was also of particular interest to me. This is a book that sits on edge between literary fiction and popular crime story of the murder-mystery kind, waiting to go off or…. There is an explosion in the end!

Ali Smith in her wonderful book Artful provides the best analysis on Edge:

Edges involve extremes. Edges are borders. Edges are very much about identity, about who you are. Crossing a border is not a simple thing. Geopolitically, getting anywhere round the world in which we live now requires a constant producing of proof of identity… Edge is the difference between one thing and another. It’s the brink. It suggests keenness and it suggests sharpness. It can wound. It can cut. It’s the blade–but it’s the blunt part of the knife too. It’s the place where two sides of a solid thing come together. It means bitterness and it means irritability, edginess, and it means having the edge, having the advantage. it’s something we can go right over… Edges are magic, too; there’s a kind of forbidden magic on the borders of things, always a ceremony of crossing over, even if we ignore it or are unaware of it.

The characters in the novel also occupy the margins, the people we may not want to acknowledge live and breathe and thrive among us because denying them is much easier. The human condition is refracted at the heart of this novel through complex motivations, why people do what they do. What we know or don’t know about nuclear testing in the Nevada Desert fuses with what we know or don’t know about South Africa’s apartheid to create newly lost and found souls. History and myth manifest in repeated performances in laboratories. Sideshows. Carnivals. Dark and light.

By the end of the book the narrator reconsiders his own research, being, the whole epistemological approach: “Maybe psychopathy was born in the heart, by shame; shame and a broken, betrayed heart.” He adds that this thought lacks “empirical exploration,” which is his expertise, but there is “a beauty to it” and a comfort that perhaps his own heart is still alive. Coincidentally, this expression evoked one of my favorite poems by Stephen Crane: In the Desert, both the literal and metaphoric sense. And isn’t it a wondrous thing that what Crane said in ten lines Abani demonstrated in 319 pages?

The difference is that Abani’s narrator doesn’t eat his heart simply because he wasn’t sure he still had it. The thought that he might yet have one is “no small miracle.” It is what redeems, releases him from the chains of his past and precarious present.

No good book is without flaws. There are common typos you’d think would be easy to fix at the editorial level, unless they occurred in House in the process of editing or typesetting. Also, some passages towards the end read like the author’s words instead of the character’s. I think to stand aside and let the characters speak without interjecting is a writer’s noble but tough wish that few accomplish. If the writers remain attached to a subject they’re writing about, then they have to make sure their prose is irresistible. But isn’t that what some writers think anyway even when the opposite is true? The reader has the last word.

No comments yet.