I did not read The Unbearable Lightness of Being but watched the movie instead. As all movies adapted from great books, I was left wondering what I had missed. Later, when I had a chance to read The Curtain, I underlined almost every sentence. I loved the plot summaries of all the books that Kundera gave. I got the sense that he truly loves literature and sharing literary works that have made a great impression on him. I was a bit disappointed not to come across women authors in his expositions. He delved into works of Defoe, Swift, Cervantes, Rabelais, Homer, Virgil, Proust, Flaubert, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Goethe, Hugo… in short, a clever mapping of European literature sprinkled here and there with the Japanese author, Kenzaburo Oe, and Latin America’s Julio Cortazar, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Carlos Fuentes, categorized under A Different Continent. But I forgave him because he liked Kafka and was bold enough to suggest that no one would have read Kafka had he written in Czech instead of German. In comparison to Germany, Czech was small context, small nation, while Germany was large context, big nation. “Kafka wrote solely in German, need we recall… But suppose for a moment he had written his books in Czech. Today who would know them?” The Curtain, page 34.

I did not read The Unbearable Lightness of Being but watched the movie instead. As all movies adapted from great books, I was left wondering what I had missed. Later, when I had a chance to read The Curtain, I underlined almost every sentence. I loved the plot summaries of all the books that Kundera gave. I got the sense that he truly loves literature and sharing literary works that have made a great impression on him. I was a bit disappointed not to come across women authors in his expositions. He delved into works of Defoe, Swift, Cervantes, Rabelais, Homer, Virgil, Proust, Flaubert, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Goethe, Hugo… in short, a clever mapping of European literature sprinkled here and there with the Japanese author, Kenzaburo Oe, and Latin America’s Julio Cortazar, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Carlos Fuentes, categorized under A Different Continent. But I forgave him because he liked Kafka and was bold enough to suggest that no one would have read Kafka had he written in Czech instead of German. In comparison to Germany, Czech was small context, small nation, while Germany was large context, big nation. “Kafka wrote solely in German, need we recall… But suppose for a moment he had written his books in Czech. Today who would know them?” The Curtain, page 34.

I began to think of national cultures in African literature that are by themselves fictions when we consider that the term “nation” is a recent invention. I also realized that the complex relationship we have with foreign languages has a lot to do with small context (nation) versus large context, national literature vis-à-vis world literature. I have a feeling that like Kafka, most popular African writers today may not have become known had they written in their mother tongues instead of say, English, French, or Portuguese. I know this is a very contentious issue and I might be stoned for saying so but personally I wouldn’t have come to know Ngugi, Achebe, Flora Nwapa, Soyinka, Ayi Kwei Ama, Ama Ata Aidoo, Mariama Ba, Marie NDiaye, and so on, had their works not been available in English. When we think of the works that are originally published in African native tongues we can hardly come up with even ten titles. This is because publishing in Africa, even in the so-called colonial languages, is not a thriving venture. Therefore, Kundera made me realize how much Africa and her literature had in common with Eastern European Literature, and the advantages of writing in a particular language within a larger context, whether we like it or not.

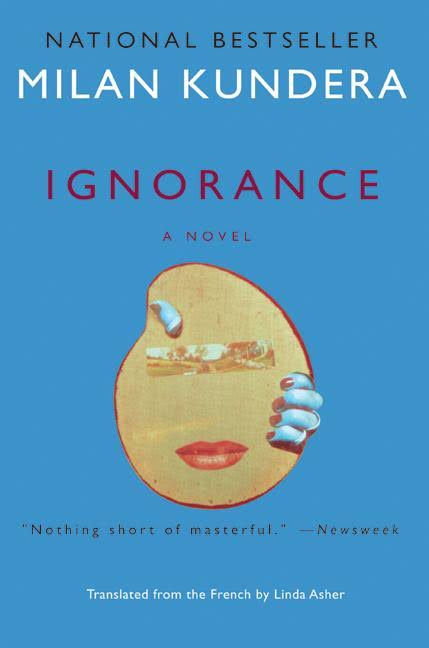

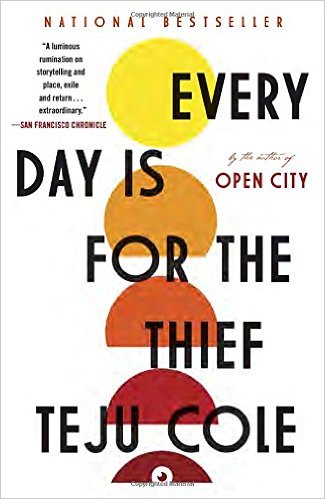

Kundera takes the language and home issues seriously in his novel, Ignorance. He focuses on the Czech’s emigrant experiences and the “Great Return” when communism comes to an end. Of course, like Odysseus, the great return is never what the characters imagine it would be. No one even asks for their stories when they arrive in Prague, gauging to see if they could stay for good or if they’d rather remain in their adoptive countries. Apparently, when Odysseus returned to Ithaca, all he wanted was someone to ask him for his story in the twenty years he’d been away, someone to say, “Tell us! And that is the one thing they never said” Ignorance, page 34. Instead, they told him what had happened in his absence, and his own accounts were insignificant. In short, that is what happens to the Czech emigrants when they go back to Czech. They’re shocked to discover that no one seems interested in their lives. What’s more, they can’t fit in because so much has changed. Permit me to mention here that Teju Cole’s narrator in Every Day Is for the Thief has a similar experience. On a visit to a former girlfriend now with a husband and child, the narrator remarks, “They don’t ask me much about myself. They do ask if I’d like lunch, and I say no” Cole, 124. All these characters have to figure out how to endure their loneliness, alienation, and make a home elsewhere.

One of the major characters in Ignorance, Irena, buys a case of Bordeaux, a rather expensive wine for her friends who had remained in Prague during the twenty years of communism. “She hopes to finally figure out whether she can live here, feel at home, have friends” page 36. Her friends, however, prefer beer, and Irena thinks that by rejecting the wine they’re rejecting her. “Irena faults herself for having lost her taste for beer; in France she learned to savor a drink by small mouthfuls, and is no longer used to bolting great quantities of liquid as beer-loving requires” 38. It is such moments that reveal how difficult Irena is trying hard to fit in, and her friends couldn’t care less. While they drink and chat boisterously, Irena can hardly get a word into the conversation. What makes matters worse is that in Prague she can no longer speak French, a language that she’s become comfortable using. English is the new currency. Knowing little English, she becomes mute, “a silent foreigner” 97.

Ignorance is one of the best emigrant experiences and diaspora/exile books I have read. As with all the Kundera books, there is a love angle but what really sustains the story is the search for home in language, people, and place.

I finished reading Ignorance at the same time I was teaching Teju Cole’s Every Day Is for the Thief, which made the focus on storytelling, place, exile and return more compelling in both books. Elements of creative nonfiction imbued with the Odyssey metaphor–“the founding epic of nostalgia…the greatest adventurer of all time” Kundera 7, characterize these two books. While Cole’s unnamed narrator has Tomas Tranströmer on his mind, “What I am looking for, what Tranströmer described as a moving spot of sun, is somewhere in the city” Cole 117, the narrator in Ignorance asks what we know is a redundant question, “Would an Odyssey even be conceivable today? Is the epic of the return still pertinent to our time?” Kundera 54. Home is at the heart of the quest. Cole’s narrator, on the plane that’s to leave Nigeria for New York says, “The word “home” sits in my mouth like foreign food. So simple a word, and so hard to pin to its meaning” Cole 156. We are told though in a moment of reflection that the narrator has found the “spot of sun” in the most unlikely place, a corridor where carpenters make coffins. “When I enter a little sun-suffused street in the heart of the district, I sense an intentionality to my being there. It feels like a return, like a center, though it is not a place I have ever been before” Cole 159. But isn’t that what a return is like, after all, to find oneself in a place you’ve never been yet know as, well, home and not home at the same time? Isn’t that what Odysseus feels when he finds himself in Ithaca, and what every returnee experiences upon arrival?

Perhaps what T.S. Eliot had in mind when he wrote Little Gidding: “We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.” We can apply this quote to knowledge, home, meaning, language, and other pursuits sought consciously only to discover what the collective unconscious has always known.

No comments yet.