A good poem is as large as a novel.

Consider this poem from Messages Left Behind, by Lupenga Mphande, published in 2011 by Brown Turtle Press.

How Long She Waited For You

Every night

She came out

And sat on the veranda, facing south

Longing for your return.

You went away many years ago,

Promising to return

With blankets and trinkets from the gold mines,

To adore your love.

Every day she flounced along village paths

Hair braided, skin oiled.

Balancing a water pot on her head,

She hummed to the wind with thoughts of you.

Then she heard from the men

That you had been enshrouded

In the bright gold reef.

Like dogs in heat they hung about her.

After so much time, what was she to think?

So, you have found her with child,

And she has given her gifts to another.

All she wants is to forget the old hours in the kraal.

It reminds me of A Grain of Wheat, a novel by Ngugi wa Thiong’o. In fact, it is the whole story in A Grain of Wheat: The times are hard, man is in jail for many years. Woman waits patiently. Eventually learns that the guy who holds the key to release needs something in return, which she can give. She misses her husband very much. The hope of return, the anticipation, the promise, oh, good news, in a rush, it’s done. She has her husband back. But then, there’s a child too. Good intention gone wrong.

I also like the way the poem hints at the challenge of being a woman in a traditional setting. The big deal being not what she did but the evidence thereof, which, of course, men do not have the burden to suffer. It makes me reflect on the imbalance and society’s double standards, not just the moral issue. We are not told what the man did when he was away all those years, we can only imagine. It’s the woman who has to bear the consequences. I could go into the whole discourse on the betrayal of the female body, but I’ll leave that for the other critics.

Hill Children

A convoy of lorries stopped by a row

of grass thatched houses by the hillside.

Soon, a swarm of half-naked children

gathered, their eyes drawn with anxiety.

Young men in green fatigues opened up

the back of the truck, and handed out

‘wanted’ posters of scraggy, bearded

men. “Have you seen these men in these

parts?” asked the captain.

The children looked at the soldiers.

No, not these soldiers, you idiots,

I mean the men on the posters!

Have you seen any one of them?”

“The children are acting mute,” said

another officer. “We all know what to do.”

“Is there anything you want, children?

Anything at all, you know: milk

chocolate, ice-cream, Fanta…you

name it?”

“Guns!” muttered one girl.

“Do you have guns?”

“We are here to pick up guerrilla

leaders,” the captain shouted to his men,

reloading his rifle.

“We have no room for children.”

Hill Children might as well be my favorite. So Chekhovian in its storytelling, especially the part where the captain is showing a picture to the children, asking if they’ve seen the men in the picture, but the children’s focus is on the captain and his men. The miscommunication, misunderstanding, or rather, missed communication, and then the seduction–some bribing–the sinister tone, and the challenge from one of the children, the girl daring, asking for guns!

I find the last stanza very dark and compelling. Thinking that I can tell where this story in the poem is going, maybe the captain reloads his rifle to shoot the children, because they’re ‘useless,’ they’ve not helped him. Or he shoots them so they don’t get to tell the scraggy men that some soldiers are looking for them. Maybe he shoots them because he’s frustrated, angry and failing in his search. Maybe he doesn’t shoot them but reloads his gun and takes off. I can’t quite decide which is which but the ambiguity is good. Lupenga has already planted troubling ideas in my head. It doesn’t matter if his words are functioning at one level or two or more.

The Spark and Death

Void

filled all space.

Chiuta, alone, inclined

in deep thought: why not

create a universe?

“There shall be universe”

Galaxy

sparked into the divide of stars;

earth, clouds, craters clattered.

Chiuta looked at earth, green,

and rose in awe at creation.

Downstream she toyed with clay,

“Let there be animals”

Woman!

‘And someone to marvel’

She said.

‘Man?’

The ultimate work to marvel

and tame the wilder work.

“There shall be woman”

Woman and man loved the world,

brought forth their own kind

In season they jaunted, viewed game

and splashed in streams. Meditation,

friction set the forest ablaze.

Vexation; retreat to heaven where

Chiuta pondered death.

Shall man be like me–

Triumph and rise?

Chameleon still fumbled in smoke

as Lizard sped past with the news:

“There shall be Death.”

Isn’t the teasing and mischief in The Spark and Death just perfect? I love that in this poem, the creator is female–‘Downstream she toyed with clay,’ even though in the Tumbuka mythology, Chiuta, the chief deity, omniscient and self-created, is portrayed as male. But then ‘he’ is symbolized in the sky by the rainbow–the Great Bow of Heaven–so what gender can a rainbow be?

Games

We play games

of hide-and-seek

at times

we do not move

do not change

but remain detached

in a world of hurt

and self-defense,

we betray each other

and are in turn

betrayed by time;

Hands extend

but at the crucifixes

do not touch

do not join.

We do not pause

we do not blink

but trample in ash

yearning for the beginning

trying instant replay

of our moments

past.

This one is sad and so true. Captures the reality of a relationship, its pretense, and then suddenly, it’s too late. A simple poem that delivers what it sets out to from the title to the subject matter.

The last of my chosen is Made of Clay. Overall it’s simple and beautiful. I like the third last line best: ‘For I, being of clay, cannot withstand the rain,’ One can say, of course, being of clay, sure, makes sense, and yet I didn’t see it coming. It’s good to be surprised, especially when the poem has the sense and structure of being simple, only to turn a clever twist.

Made of Clay.

If I came to you now, ejected by the landlord,

With only my tattered dream covering my body,

Would you bathe me, clothe me, give me shelter?

For I come with nothing, except my love for you.

Grasp the knobkerrie and stones

And let us resist the landlords,

For I, being of clay, cannot withstand the rain,

However gentle the wind.

There are sixty-four poems in this collection, varying in length, tone and style. They cut across categories such as Nature, Love, Political poems, Traditional, Spark of judgment, and Children of the Kalahari. Always a joy to read and discover good poems.

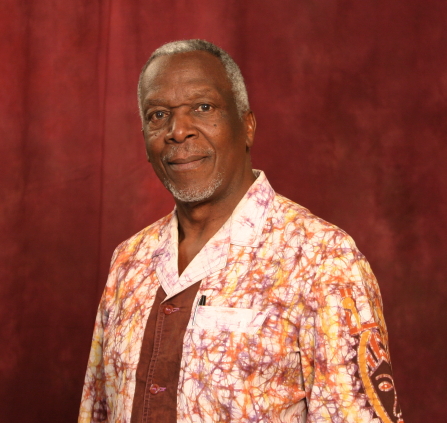

Lupenga Mphande was born in Malawi, and is currently the Associate Professor of African and African American Studies at Ohio State University in Columbus. Click here to order your copy of Messages Left Behind.

No comments yet.