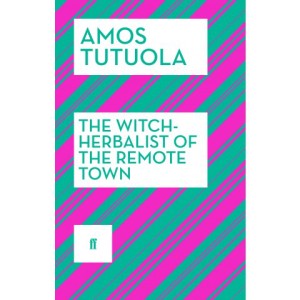

I’m inclined to experiments in reading. I will sometimes read five books concurrently, and to avoid mixing the stories, I will select two books in poetry, two in fiction, and one nonfiction. The mind can handle an evolutionary biology text alongside Ezra Pound, Teju Cole, Charles Simic and Ali Smith. Surprisingly–and this is partly why i love to read this way, i discover connections, similarities, and shared opinions amongst the writers in ways i would never have imagined or entertained. It’s become a good challenge for me to sniff out the differences and similarities across history, regions, cultures, periods, styles, and so on. Being a lover and student of literature facilitates my dissections in such a way that i always can prove what i set out to find, and this aspect is the difference between arts and sciences. In the humanities, at least, we can always prove that yes, connections exist between Don Quixote and The Palm Wine Drinkard, that The Odyssey and The Witch-Herbalist of the Remote Town tell the same story, only that one is set in the wilderness and towns of Nigeria, while the other is in Greece. In the sciences this isn’t the case, generally speaking. While I do not want to simplify how we read, or what might be an easy approach to analyzing texts in the humanities, what I would like to emphasize is the active process of reading, how our minds rejoice in finding connections, how they participate and explain texts to us in ways that surprise and make sense at the same time, in ways we would not normally anticipate had we not been present with our minds, watching, witnessing, and taking in the work being done.

I’m inclined to experiments in reading. I will sometimes read five books concurrently, and to avoid mixing the stories, I will select two books in poetry, two in fiction, and one nonfiction. The mind can handle an evolutionary biology text alongside Ezra Pound, Teju Cole, Charles Simic and Ali Smith. Surprisingly–and this is partly why i love to read this way, i discover connections, similarities, and shared opinions amongst the writers in ways i would never have imagined or entertained. It’s become a good challenge for me to sniff out the differences and similarities across history, regions, cultures, periods, styles, and so on. Being a lover and student of literature facilitates my dissections in such a way that i always can prove what i set out to find, and this aspect is the difference between arts and sciences. In the humanities, at least, we can always prove that yes, connections exist between Don Quixote and The Palm Wine Drinkard, that The Odyssey and The Witch-Herbalist of the Remote Town tell the same story, only that one is set in the wilderness and towns of Nigeria, while the other is in Greece. In the sciences this isn’t the case, generally speaking. While I do not want to simplify how we read, or what might be an easy approach to analyzing texts in the humanities, what I would like to emphasize is the active process of reading, how our minds rejoice in finding connections, how they participate and explain texts to us in ways that surprise and make sense at the same time, in ways we would not normally anticipate had we not been present with our minds, watching, witnessing, and taking in the work being done.

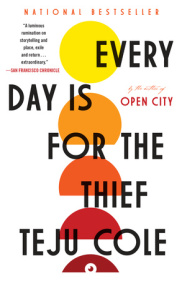

My latest experiment is reading a book from the early periods alongside a contemporary text, and discovering conversations between the two. For instance, Gilgamesh is very much alive in Chris Abani’s Sanctificum and The Secret History of Las Vegas. Teju Cole’s unnamed narrator in Every Day is for the Thief discovers Sheherazades in Nigeria, and by so doing the reader sees the Arabian Nights, not just metaphorically but stylistically as well. “Lagos is a city of Scheherazades. The stories unfold in ever more fanciful iterations and, as in the myth, those who tell the best stories are richly rewarded.” But in my head something more uncanny happens when I put aside Every Day is for the Thief and dive into Amos Tutuola’s The Witch-Herbalist of the Remote Town. It’s early afternoon, I’m lying on my blue couch in the living room. I notice the journey motif that both writers employ. Tutuola is magical and humorous, stylistically, while Cole is realistic and memoir-like. Cole’s character leaves New York City and returns to a home he doesn’t recognize in Nigeria. He has changed so has everything. He goes into the depths of the city in search of what he can hold onto. In a way he’s a mini-version of Odysseus looking for Ithaca which no longer exists in the form he left it. He finds something tucked away on a street where coffin makers do their trade. It soothes him. Tutuola’s unnamed character is “a born and die baby,” meaning, he belongs elsewhere in the world of spirits. His earthly father is the chief priest of the oracle, so he does the right sacrifice and behold, the earthly mother claims and gives birth to a son. Already a special person, this son in his twenties leaves his town in search of a cure for his wife (but it’s really his journey) and traverses the jungles, battling beasts, giants, and wild animals. In due course he finds both a return and departure from home.

My latest experiment is reading a book from the early periods alongside a contemporary text, and discovering conversations between the two. For instance, Gilgamesh is very much alive in Chris Abani’s Sanctificum and The Secret History of Las Vegas. Teju Cole’s unnamed narrator in Every Day is for the Thief discovers Sheherazades in Nigeria, and by so doing the reader sees the Arabian Nights, not just metaphorically but stylistically as well. “Lagos is a city of Scheherazades. The stories unfold in ever more fanciful iterations and, as in the myth, those who tell the best stories are richly rewarded.” But in my head something more uncanny happens when I put aside Every Day is for the Thief and dive into Amos Tutuola’s The Witch-Herbalist of the Remote Town. It’s early afternoon, I’m lying on my blue couch in the living room. I notice the journey motif that both writers employ. Tutuola is magical and humorous, stylistically, while Cole is realistic and memoir-like. Cole’s character leaves New York City and returns to a home he doesn’t recognize in Nigeria. He has changed so has everything. He goes into the depths of the city in search of what he can hold onto. In a way he’s a mini-version of Odysseus looking for Ithaca which no longer exists in the form he left it. He finds something tucked away on a street where coffin makers do their trade. It soothes him. Tutuola’s unnamed character is “a born and die baby,” meaning, he belongs elsewhere in the world of spirits. His earthly father is the chief priest of the oracle, so he does the right sacrifice and behold, the earthly mother claims and gives birth to a son. Already a special person, this son in his twenties leaves his town in search of a cure for his wife (but it’s really his journey) and traverses the jungles, battling beasts, giants, and wild animals. In due course he finds both a return and departure from home.

Cole and Tutuola have written stories of fathers but they’re also stories of sons placed in the larger context of countries, how they progress through time, and the creative resources available. The mothers occupy a strange territory. In the chapter of the “Long-Breasted Mother of the Mountain” page 66, I come across the sentence: “Yes, all days are for the thief to steal but one day is for the owner of the property to catch him!” I go back to Cole’s book, to the section which acknowledges that his title is from a Yoruba proverb: “Every day is for the thief, but one day is for the owner.” Fair enough, we all have access to the proverbs, we can call them public property, but isn’t it truly bizarre that i would read the proverb in Tutuola’s book just at the time I’m reading Cole, going back and forth, when from the beginning I had no clue that I would stumble upon such a connection? Isn’t this discovery truly delightful? Even if I wasn’t interested in connections, even if this small “coincidence” might mean nothing, how can i ignore it? Aren’t these two books in conversation? Isn’t it what good literature does? Isn’t it the purest joy in my afternoon? Hasn’t it given me pleasure? Aren’t i now smiling, ecstatic even…blogging about it? If this isn’t enough to make us love books madly, what then? But who am I arguing with, trying to convince?

No comments yet.